Fresenius Kabi announced today that it has received 510(k) regulatory clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its wireless Agilia® Connect Infusion System which includes the Agilia Volumetric Pump and the Agilia Syringe Pump with Vigilant® Software Suite-Vigilant Master Med technology. Both pumps are the first to be cleared by following TIR101 standards, which were developed by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) in 2021. The product offering for hospitals and clinics enables the centralized distribution of drug libraries, warehousing of infusion data for reporting and analysis, and wireless maintenance and calibration of devices. The clearance is an important milestone for the company’s infusion therapy business in the U.S.

The Supervisory Board of Fresenius SE & Co. KGaA will propose that the next Annual General Meeting on May 13, 2022 elect Dr. Christoph Zindel, 60, to the Supervisory Board. If elected, he will also join the Supervisory Board’s Audit Committee. As announced last year, Klaus-Peter Müller, 77, will leave the Supervisory Board at the end of the Annual General Meeting and turn over the Audit Committee’s chairmanship to Susanne Zeidler, 61. The next regular election of all shareholder representatives is scheduled for the 2025 Annual General Meeting.

Dr. Zindel has been a member of the Siemens Healthineers Managing Board since October 2019. He began his career as a practicing physician in surgery, internal medicine and nuclear medicine, before moving into the healthcare industry in 1998 as a Segment Manager at Siemens Healthcare. There he held various management positions in the magnetic resonance-tomography business division. After three years in the U.S., lastly as head of the Business Unit Hematology and Urinanalysis at Beckman Coulter in Miami, he returned to Siemens Healthineers in 2015 and headed the Business Line Magnetic Resonance. In 2018, Dr. Zindel was appointed President Diagnostic Imaging.

Klaus-Peter Müller has been a Member of the Supervisory Board of Fresenius SE (today Fresenius SE & Co. KGaA) and its Audit Committee since 2008. From 2010 until 2021 he also belonged to the Supervisory Board of Fresenius Management SE. A highly regarded financial expert, Klaus-Peter Müller worked at Commerzbank AG from 1966 to 2008 and served from 2001 to 2008 as Chief Executive Officer.

Wolfgang Kirsch, Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Fresenius, said: “Dr. Christoph Zindel has a background in medicine, extensive international experience and comprehensive knowledge of the healthcare industry. This makes him an outstanding addition to our Board. As for Klaus-Peter Müller, on behalf of the Supervisory Board I want to thank him for his long connection with Fresenius and his many important contributions to our success.”

This release contains forward-looking statements that are subject to various risks and uncertainties. Future results could differ materially from those described in these forward-looking statements due to certain factors, e.g. changes in business, economic and competitive conditions, regulatory reforms, results of clinical trials, foreign exchange rate fluctuations, uncertainties in litigation or investigative proceedings, and the availability of financing. Fresenius does not undertake any responsibility to update the forward-looking statements in this release.

Information on the Annual General Meeting

Invitation / Agenda

Information for shareholders

Information on scrip dividend

Information on the agenda item

Additional Information

Further publications

The European Commission (EC) has granted Fresenius Kabi the marketing authorization for Stimufend®, the company’s pegfilgrastim biosimilar, for all approved indications of the reference medicine. Stimufend® stimulates the growth of certain white blood cells, which are essential to prevent or fight infections, a common life-threatening risk in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. This is the company’s first approved biosimilar molecule used in oncology and its second biosimilar approved in Europe, expanding its autoimmune disease and oncology focused product portfolio.

- First steps in executing Fresenius Kabi’s “Vision 2026” growth strategy

- Acquisition of majority stake in mAbxience significantly enhances Fresenius Kabi’s presence in high-growth biopharmaceuticals market

- Ivenix adds next-generation infusion therapy platform to transform product offering

- Combined, these acquisitions will meaningfully increase the company’s scale over the next years and accelerate the Group’s growth

- Acquisitions combined are expected to be broadly neutral to Group cash earnings per share1 in 2022 and accretive by 2023

- Transactions expected to close by mid-2022

1 earnings before amortization and integration costs

Stephan Sturm, CEO of Fresenius, said: “Through these acquisitions we are further strengthening and leveraging Fresenius Kabi's position, as both perfectly complement the company's growth businesses in biopharmaceuticals and medical technology. We will continue allocating capital in a targeted manner to rigorously pursue the recently presented growth strategy of our health care Group which has defined Fresenius Kabi as top priority. In this way, we are creating even better conditions for providing ever better medicine to ever more people. At the same time, we create meaningful value for our shareholders.”

Michael Sen, CEO of Fresenius Kabi, said: “Expanding our MedTech business and broadening our presence in Biopharmaceuticals are key to our Vision 2026 program. Today’s announcements fit squarely into our plans. With the acquisition of Ivenix, we add the next generation infusion therapy platform; we complement and strengthen our existing infusion therapy offering and we create a superior portfolio for the US market. With mAbxience, we are making a step-change in our biopharmaceuticals profile. This is a highly complementary transaction in terms of biologics pipeline, manufacturing capabilities and the business model. mAbxience is two businesses in one company. mAbxience and Ivenix as portfolio advancements are good for patients, good for healthcare providers and our company.”

Acquisition of a majority stake in mAbxience significantly enhances Fresenius Kabi’s presence in high-growth biopharmaceuticals market

- Delivers on core growth vector “Broaden Biopharma” of “Vision 2026”

- Provides access to expertise and capabilities in one of the fastest-growing areas of healthcare, positioning Fresenius Kabi for accelerated medium- and long-term growth

- Follows a convincing industrial logic focused on a global, end-to-end vertically integrated biopharmaceuticals footprint

- Creates a strong partnership with excellent growth potential in attractive biosimilars market

- Comprises high-growth biologics Contract Development and Manufacturing (“CDMO”) market with three state-of-the-art biologics manufacturing facilities in Spain and Argentina

- Provides access to a highly cost competitive biologics manufacturing capacity with significant cost synergies expected for Fresenius Kabi’s biosimilars portfolio

Fresenius Kabi announced today that it has agreed to acquire a stake of 55% of mAbxience Holding S.L. (”mAbxience”). The purchase price will be a combination of €495 million upfront payment and milestone payments, strictly tied to the achievement of commercial and development targets. The contractual provisions also include a put / call option scheme regarding the current owners’ remaining shares in mAbxience (45%).

mAbxience is a leading international biopharmaceutical company, focused on the rapidly developing biosimilars market. The company was founded in 2010 by Dr. Hugo Sigman and Dr. Silvia Gold as the biotechnology division of Insud Pharma S.L. mAbxience has established itself as a leader in the development and manufacturing of biological drugs, with two commercialized biosimilar products (Rituximab and Bevacizumab) and a mid-single-digit number of molecules across immunology and oncology expected to be launched globally in the years 2024 to 2029. This is supported by internal R&D laboratories and state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities in Spain and Argentina. In addition to highly competitive production costs for the internal programs, the manufacturing platform allows mAbxience to offer third party biological CDMO services, including a recent contract with AstraZeneca to produce the drug substance for its COVID-19 vaccine in Latin America. The company currently employs approximately 600 staff and generated sales of approx. €255 million in 2021.

The acquisition of a majority stake in mAbxience follows Fresenius Kabi’s recently unveiled Vision 2026 strategy, delivering on one of the core growth vectors – to “Broaden Biopharma” – by expanding along the value chain and further enhancing the existing Fresenius Kabi biosimilars pipeline.

Fresenius Kabi expects, through its in-house biosimilars programs and through its investment in mAbxience, to capture an overproportionate share of the underlying rapid growth in the biopharmaceutical market. Fresenius Kabi’s footprint in biopharmaceuticals will be significantly strengthened by broadening its biosimilars portfolio and by gaining access to the distinctive manufacturing capabilities of mAbxience. It will also allow Fresenius Kabi to provide end-to-end integrated biopharmaceutical solutions for customers from its state-of-the-art facilities.

mAbxience operates three state-of-the-art facilities for the production of biologic drug substance. This addresses a critical gap in Fresenius Kabi’s value chain, adding flexible, single-use biologic drug substance capacity that can be leveraged to provide competitive cost of production for the enlarged biosimilars portfolio. This manufacturing capability also offers end-to-end integrated biopharmaceutical solutions for customers and thus establishes a strategic foothold for Fresenius Kabi in the fast-growing biologic CDMO sector, complementing the existing small molecule API and fill & finish operations.

Once completed, the transaction is expected to deliver material operating and cost synergies for Fresenius Kabi, primarily driven by leveraging mAbxience’s manufacturing capabilities for Fresenius Kabi’s existing biosimilars business.

The transaction remains subject to regulatory approvals and other customary closing conditions and is expected to close by mid-2022.

Ivenix strengthens Fresenius Kabi’s MedTech business and accelerates growth

- Delivers on core growth vector “Expand MedTech” of Vision 2026

- Provides next-generation infusion therapy platform for U.S. market

- Complements Fresenius Kabi’s global infusion therapy offering

- Provides Fresenius Kabi with key capabilities in hospital connectivity and creates new options for growth of MedTech business

- Significant scale and growth synergies expected

Fresenius Kabi announced today that it has agreed to acquire Ivenix, Inc. („Ivenix“), a specialized infusion therapy company. The purchase price will be a combination of US$240 million upfront payment and milestone payments, strictly linked to the achievement of commercial and operating targets.

Ivenix is a privately held company based in North Andover, Massachusetts, USA. The company has developed the technologically most advanced infusion system including a large volume pump (“LVP”) with administration sets, infusion management software tools, applications and analytics to inform care and advance efficiency. The Ivenix Infusion System’s innovative design and architecture sets a new standard in infusion safety, simplicity and interoperability. The system is centred around the patient and clinician and is designed to reduce infusion-related errors and drive down the total cost of ownership. After having received the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval, the Ivenix Infusion System was successfully launched in late 2021.

Ivenix’ Infusion System provides access to attractive growth potential for Fresenius Kabi in the large and growing infusion therapy market. The combination of Ivenix’ leading hardware and software products with Fresenius Kabi’s offerings in intravenous fluids and infusion devices will create a comprehensive and leading portfolio of premium products, forming a strong basis to enable sustainable growth in the high-value MedTech space.

The transaction is subject to regulatory approvals and other customary closing conditions and is expected to close by mid-2022.

Financing and implications on Group financials

mAbxience is expected to be accretive to Group cash earnings per share (earnings before amortization and integration costs) right after closing. Ivenix is expected to be neutral to Group cash earnings per share in 2025 and accretive from 2026 onwards.

Combined, these acquisitions are expected to be broadly neutral to Group cash earnings per share in 2022 and accretive as of 2023.

The transactions are currently expected to be financed by cash flow and available liquidity.

Conference Call

A telephone conference on the acquisition of a majority stake in mAbxience Holding S.L. and the acquisition of Ivenix, Inc. will be held on March 31, 2022 at 1:30 p.m. CEST (7:30 a.m. EDT). All investors are cordially invited to follow the conference call in a live broadcast over the Internet at www.fresenius.com/investors. Following the call, a replay will be available on our website.

This release contains forward-looking statements that are subject to various risks and uncertainties. Future results could differ materially from those described in these forward-looking statements due to certain factors, e.g. changes in business, economic and competitive conditions, regulatory reforms, results of clinical trials, foreign exchange rate fluctuations, uncertainties in litigation or investigative proceedings, the availability of financing and unforeseen impacts of international conflicts.

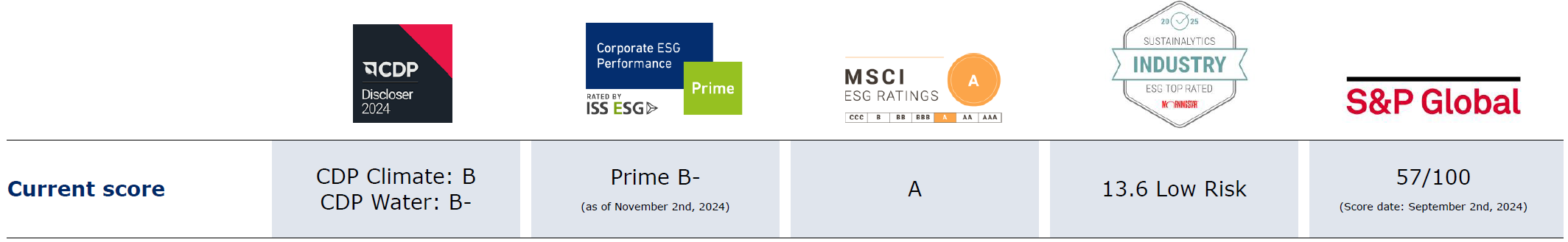

Continuous improvement through reporting and engagement

The leading ESG rating agencies regularly evaluate and review Fresenius' sustainability performance. An intensive dialog on all ESG (environmental, social, governance) topics is very important to us.

We are working decisively to further increase transparency on all topics relevant to our stakeholders.

*The use by FRESENIUS SE & CO. KGAA ofany MSCI ESG RESEARCH LLC or its affiliates (“MSCI”) data, and the use of MSCI logos, trademarks, service marks or index names herein, do not constitute a sponsorship, endorsement, recommendation, or promotion of FRESENIUS SE & CO. KGAA by MSCI. MSCI services and data are the property of MSCI or its information providers, and are provided ‘as-is’ and without warranty. MSCI names and logos are trademarks or service marks of MSCI.

*Copyright © 2025 Morningstar Sustainalytics. All rights reserved. This publication contains information developed by Sustainalytics (www.sustainalytics.com). Such information and data are proprietary of Sustainalytics and/or its third party suppliers (Third Party Data) and are provided for informational purposes only. They do not constitute an endorsement of any product or project, nor an investment advice and are not warranted to be complete, timely, accurate or suitable for a particular purpose. Their use is subject toconditions available at https://www.sustainalytics.com/legal-disclaimers.

Contact

If you have any questions about sustainability, please contact us:

sustainability@fresenius.com