Más de askFresenius

¿Tiene alguna pregunta? askFresenius encuentra la respuesta. O a alguien que la sepa. Tras nuestra plataforma interna de conocimiento se esconde un algoritmo de autoaprendizaje que traslada su pregunta al colega o la colega adecuados de forma automática.

askFresenius es la plataforma de conocimiento de todo el Grupo Fresenius. Todo el mundo puede participar, independientemente del departamento de la empresa o de la región. Lo mejor: obtiene las respuestas a sus preguntas y establece nuevos contactos.

Por cierto: el idioma no es un problema. Con la función de traducción puede traducir a su idioma cualquier pregunta y cualquier respuesta.

Aquí puede acceder a askFresenius:

Y así se inicia sesión:

|

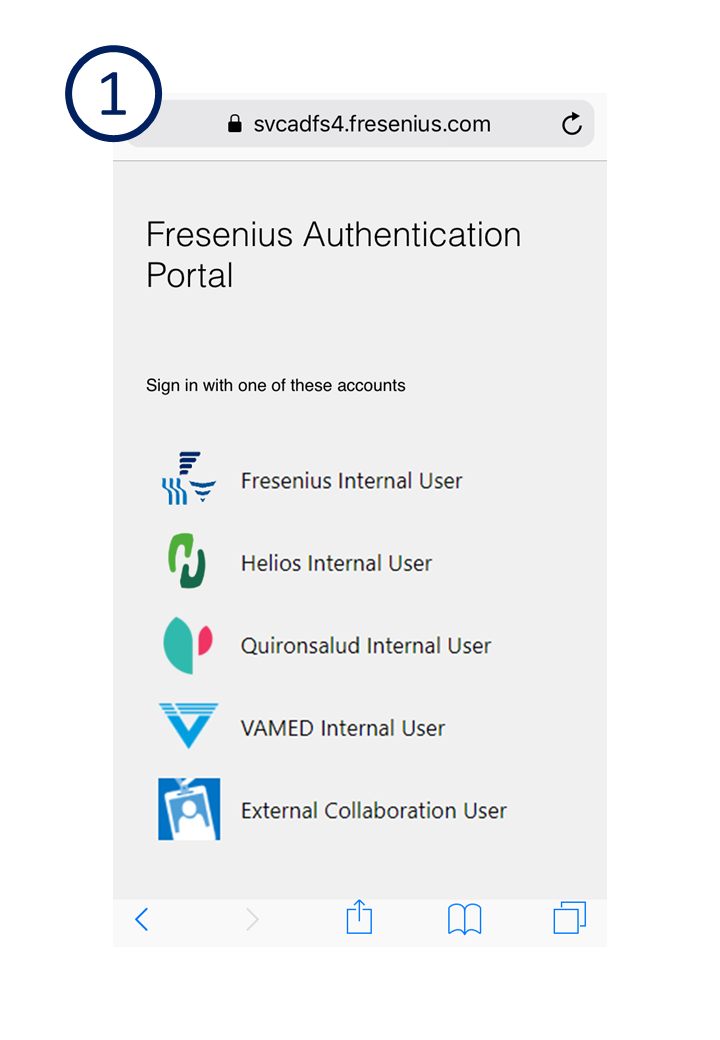

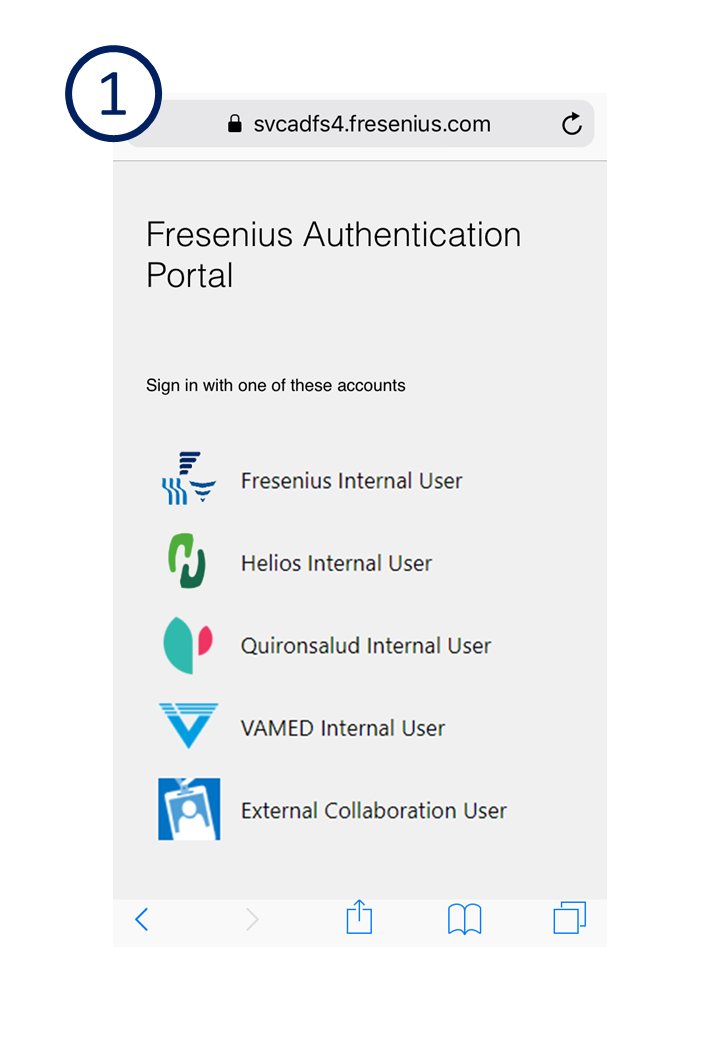

Acceda a askfresenius.com desde su navegador y seleccione su empresa:

Si trabaja en Fresenius, Fresenius Kabi o Fresenius Digital Technology, haga clic en “Fresenius Internal User”. |

|

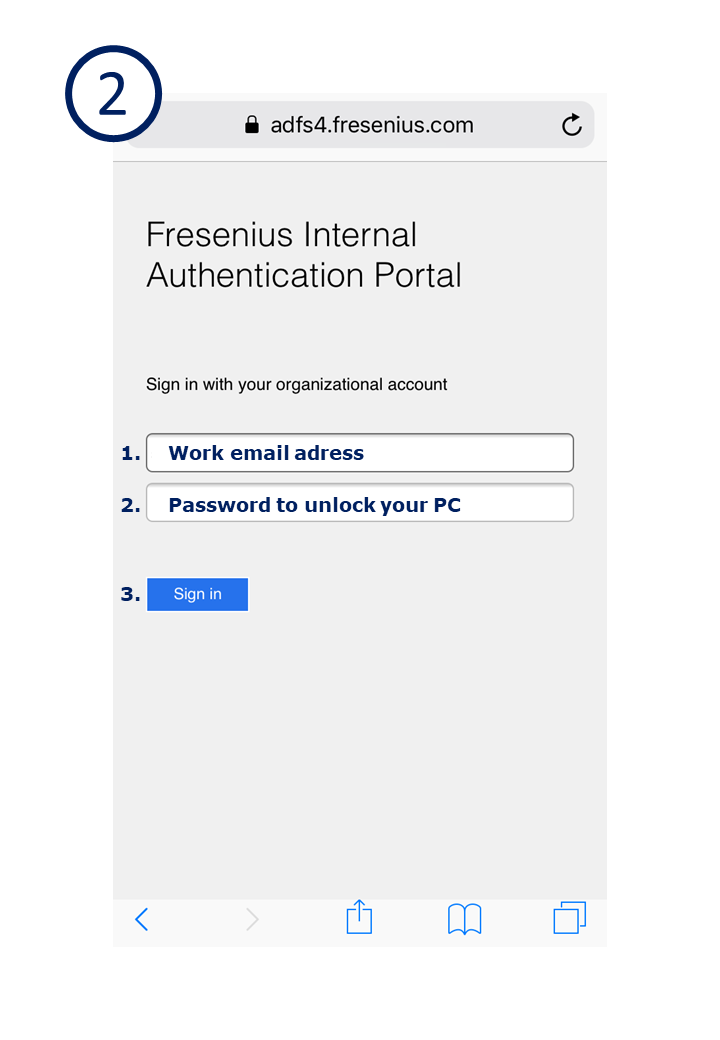

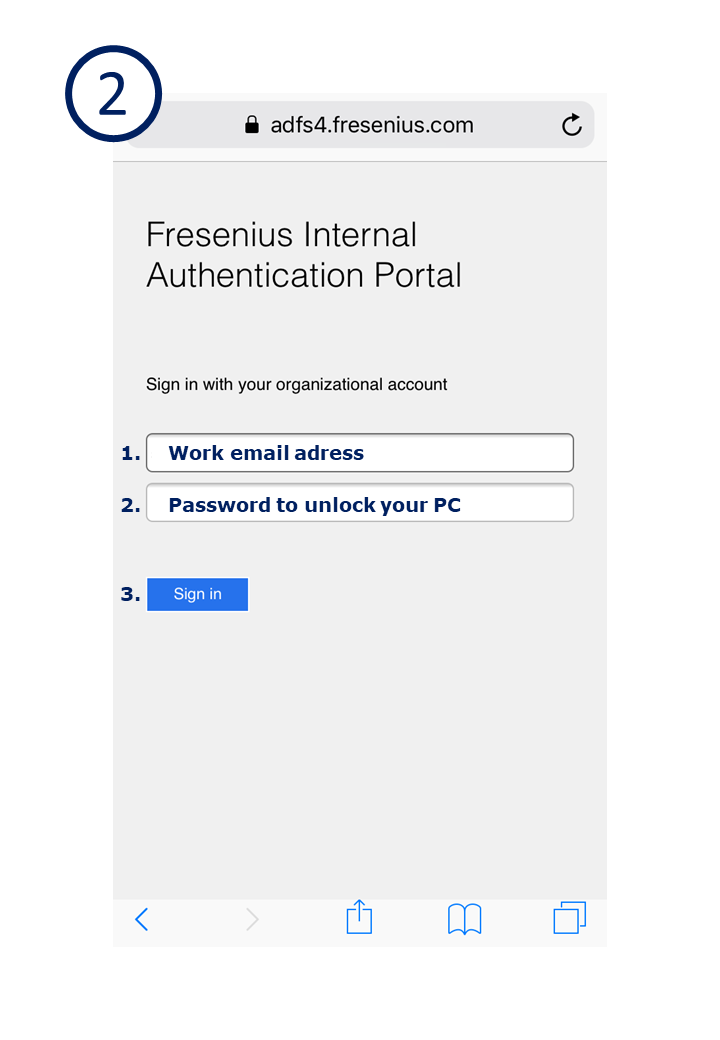

En el campo superior, introduzca su dirección de correo electrónico profesional.

En el campo inferior, introduzca la contraseña de su ordenador.

¡Disfrute del intercambio de conocimiento en askFresenius! |

Contacto

Video Placeholder

The video "Más de askFresenius" needs to be inserted here.

Enlace

askfresenius.starmind.comMás información

¿Necesita más información o quiere que presenten askFresenius a su equipo?

Le invitamos a un webinario en su idioma. Escríbanos a ask@fresenius.com.

Usuarios externos

¿Desea acceder a askFresenius pero no trabaja en Fresenius? A nuestra red interna y global de conocimiento solo tienen acceso las empleadas y los empleados. ¡Pero es posible que pueda saludarnos pronto! Aquí encontrará vacantes.

Vous avez une question? askFresenius trouvera la réponse. Ou quelqu’un qui la connait. Derrière notre plateforme de mise en commun des connaissances interne se cache un algorithme autoadaptatif qui transmet automatiquement votre question aux collègues susceptibles de connaître la réponse.

askFresenius est la plateforme de mise en commun des connaissances disponible pour tous au sein du groupe Fresenius. Ici, chacun peut participer : quel que soit votre domaine au sein de l’entreprise ou votre région. Et pour couronner le tout: vous obtenez des réponses à vos questions et établissez de nouveaux contacts.

La langue ne constitue pas un obstacle: grâce à la fonction de traduction, vous pouvez traduire vos questions ainsi que les réponses dans votre langue.

Comment se connecter :

| Allez sur la page askfresenius.com et sélectionnez votre entreprise.

Si vous travaillez pour Fresenius, Fresenius Kabi ou Fresenius Digital Technology, veuillez cliquer sur « Fresenius Internal User ».

Si vous travaillez pour une autre division, veuillez cliquer sur le nom de l'entreprise. |

| Saisissez ici dans le champ supérieur votre adresse e-mail de l'entreprise.

Entrez ensuite dans le champ inférieur le mot de passe avec lequel vous déverrouillez votre PC.

Nous vous souhaitons un échange de connaissances fructueux avec askFresenius ! |

Contact

Video Placeholder

The video "Bon à savoir" needs to be inserted here.

Pour plus d’infos

Vous avez besoin d’informations supplémentaires ou vous souhaitez bénéficier d’une présentation d’askFresenius pour votre équipe ?

Nous nous ferons un plaisir de vous inviter à prendre part à un webinaire dans votre langue. Écrivez-nous à ask@fresenius.com.

Utilisateurs externes

Vous souhaitez avoir accès à askFresenius, mais vous ne travaillez pas chez Fresenius ? Seuls nos collègues ont accès à notre plateforme de mise en commun des connaissances interne et internationale. Mais peut-être pourrons-nous bientôt vous accueillir parmi nous. Vous trouverez ici nos offres d’emploi.

Contact

Fresenius SE & Co. KGaA

Else-Kröner-Str. 1

61352 Bad Homburg

Germany

T: +49 6172 608-0

pr-fre@fresenius.com

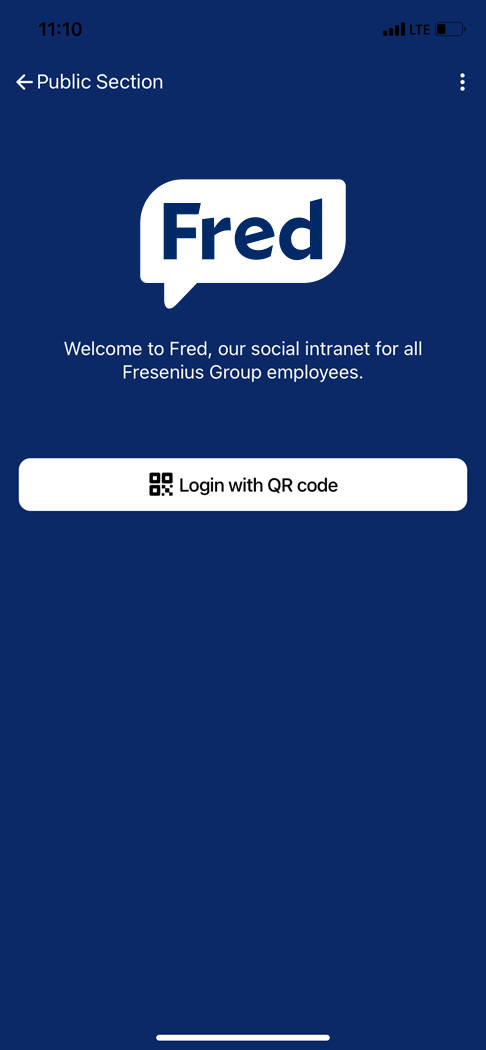

Want to stay up to date wherever you go, share, like and comment on important information with your colleagues?

Simply reach for your smartphone or tablet, because Fred is also available as an app!

Interested?

Download the Fred app now and get started!

The Fred app at a glance

With news from the entire Fresenius Group, you can always be up to date, even when you’re away from your desk

With news from the entire Fresenius Group, you can always be up to date, even when you’re away from your desk

![]() Keep track of all chats you have access to

Keep track of all chats you have access to

1. Download the app

The installation procedure differs depending on which device you use:

Alternatively, you can also download the Fred app from your company's own app store.

For all devices, then open the app and allow it to access the camera. You can only log in if the app has camera access.

2. Log in via QR code

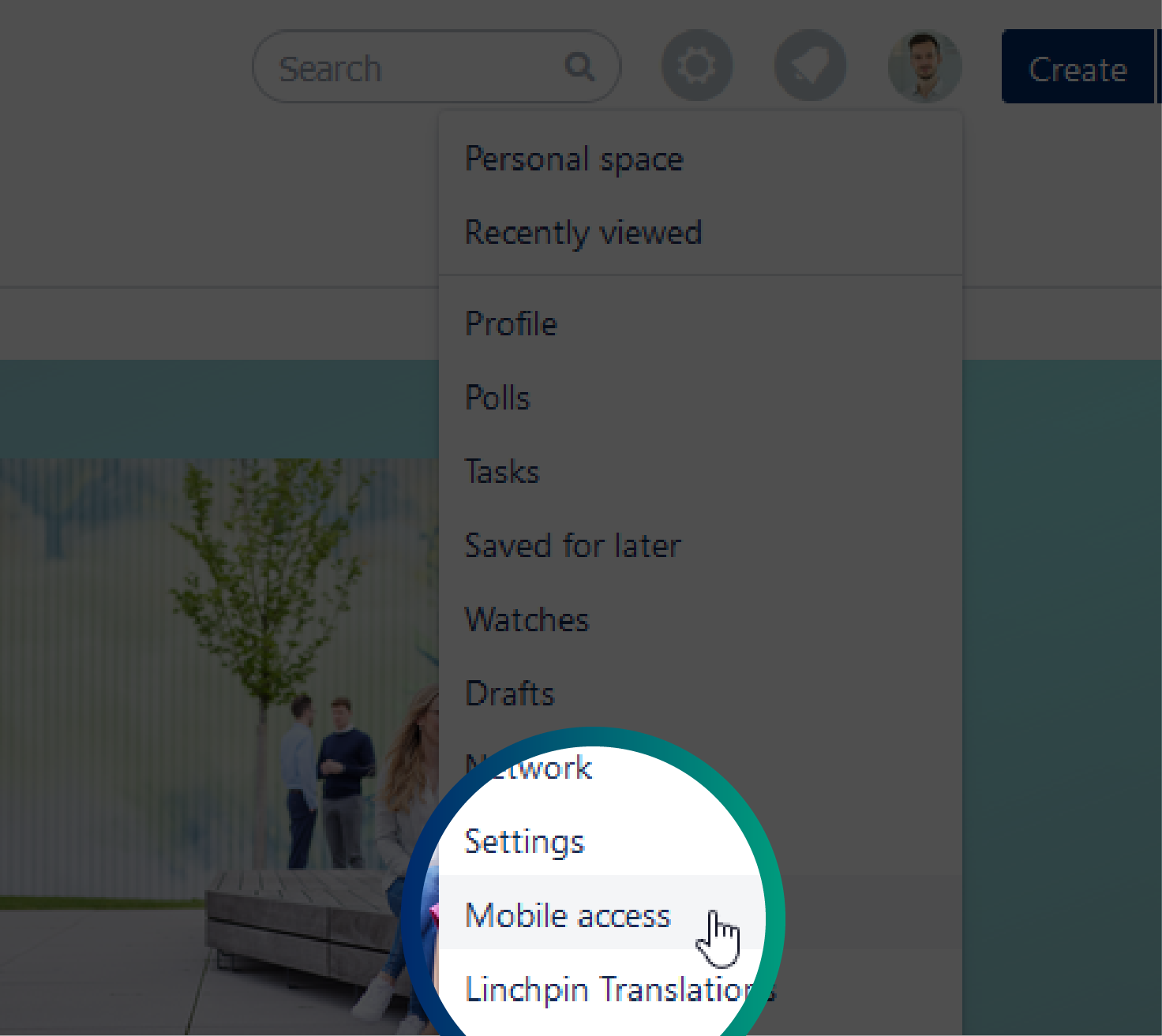

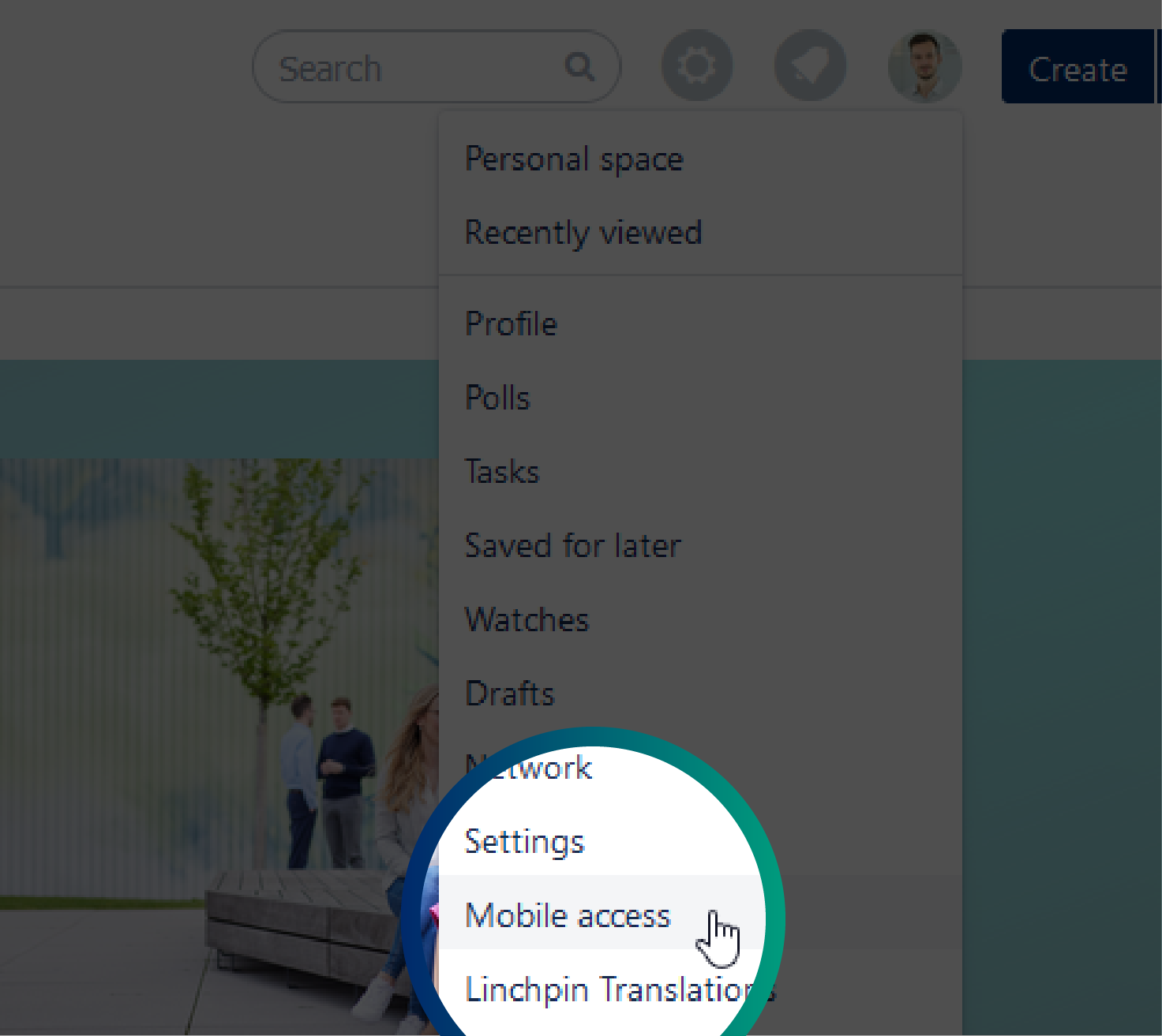

For the first login you will need a QR code. To get this, open your Fred profile on your laptop. Click your profile picture at the top right of the home page.

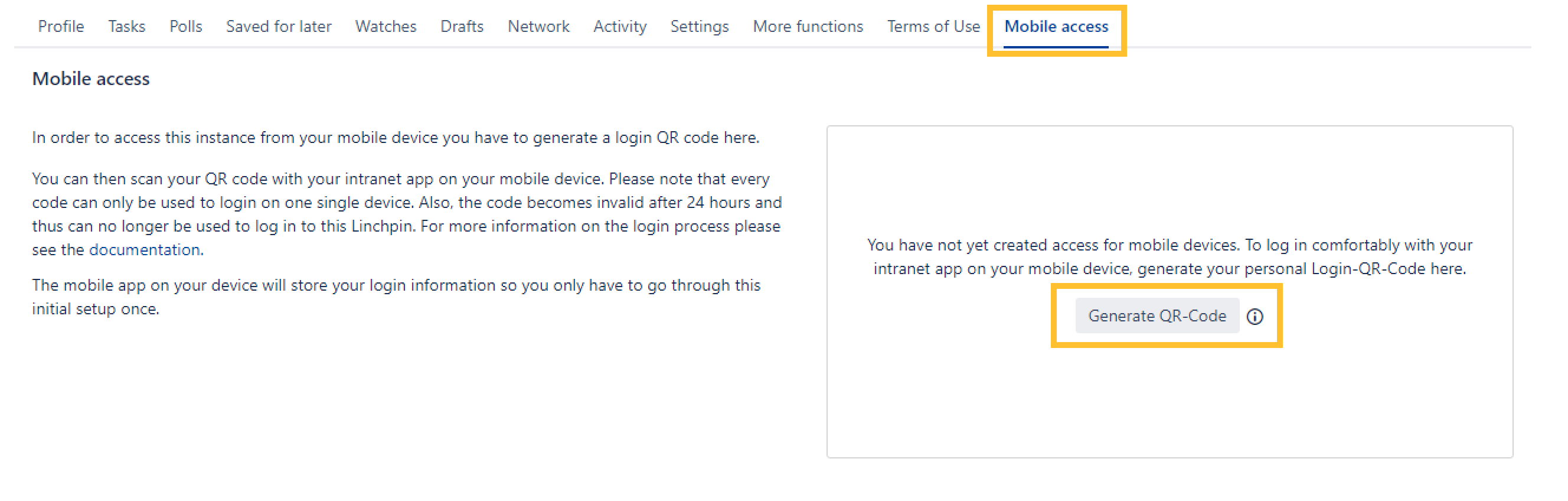

On the list under your profile picture, select the Mobile Access tab:

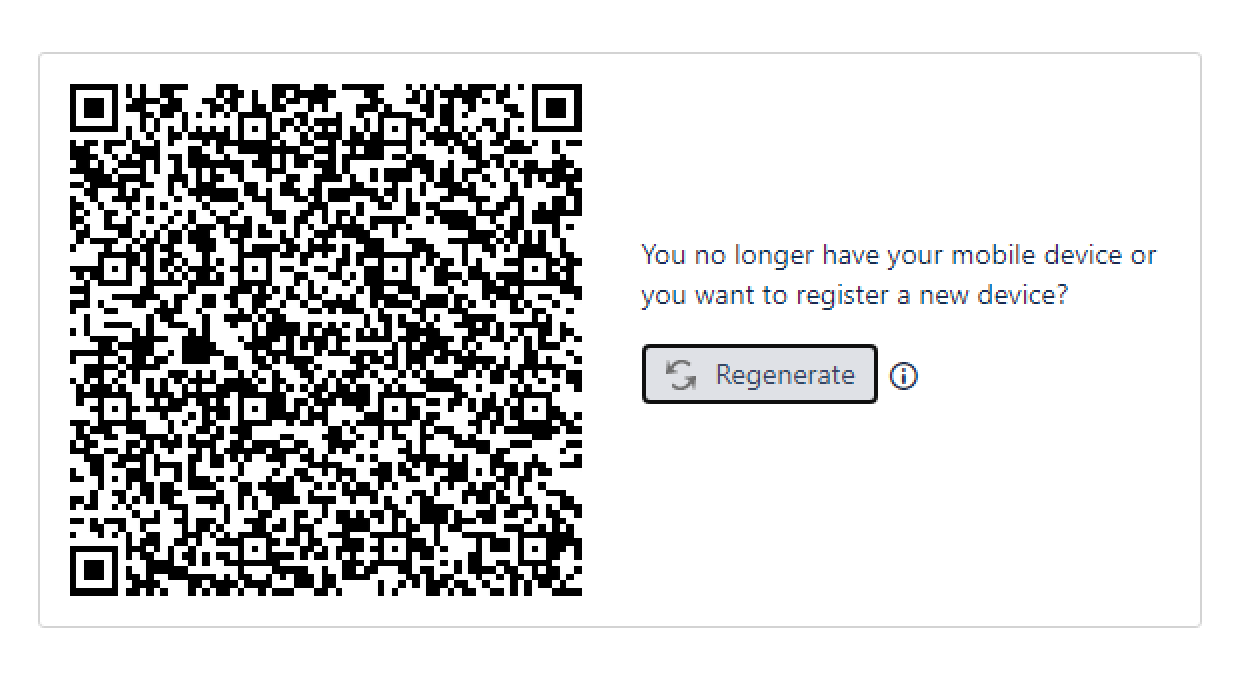

Click Create QR code to generate your personal code.

3. Get started

When you start the app, you will see this screen. Please click "Login with QR code".

Now you are good to go – you can use Fred anytime, anywhere with your business smartphone or tablet.

Fred app - FAQ's

Access, login and language

The only requirement for using the Fred app on your personal mobile device is that you have an Active Directory account and have already logged into Fred on the desktop version.

The following links will take you directly to the download

Apple: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/fred-mobile/id1489331237

Android: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.fresenius.fred

|

1. When you start the app, you will see this screen. Please click "Login with QR code". |

|

2. Open Fred in parallel on the personal computer. Click on your profile picture on the top right and select "Mobile access" from the dropdown. |

| 3. Generate a QR code for yourself. Each QR code is valid only for one device and for 24 hours. |

| 4. Scan the generated QR code with your company smartphone or tablet. You will now be redirected to the app. Have fun! |

Please report your problem via our Service Desk at globalservicedesk@fresenius.com or contact the support hotline in your country. You can find the correct number on this page https://fnc.service-now.com/sp?id=kb_article&sysparm_article=KB0012329&sys_kb_id=08dbec2e1bb8a410f22763546b4bcb5bunder the menu item "Fred". For example, if you work in Germany, please call +49 6172 608 1111.

The Fred menu is available either in English or German language. The menu language of the app depends on the language setting of your mobile device: If German is set, you will see the Fred app with a German menu. If you have another language on your device, you will see the app in English.

Functions

The Fred app does not replicate the desktop version 1:1, but does offer some of Fred’s core features. You can:

- Read news from all business segments

- Create and comment on bulletin board entries

Please note that some functionalities (so-called macros) are not available in the Fred app. However, for some macros you have the option to switch to the desktop version on your mobile device and view the content.

| Eye: Specify whether you want to “watch” specific pages. If you watch a page, you will be informed by email about changes to the page, and always stay up to date on it. We've summarized how to edit your watch list in the desktop version here. |

| Share icon: You find a certain page interesting? Share it quickly and easily with colleagues. The people you select will then receive an email with the link to the page. You can even add a personal message. |

|

The menu item "Microblog" shows you an overview of all posts of the chats that you can access. Using the funnel icon at the top right, you can define which chats should be displayed to you in the future. This way, you can subscribe to the chats that you consider relevant – and remove ones that are not of interest to you.

You can find the bulletin board via the menu item "Microblog." There you can see all the posts from the chats you can access – including the bulletin board.

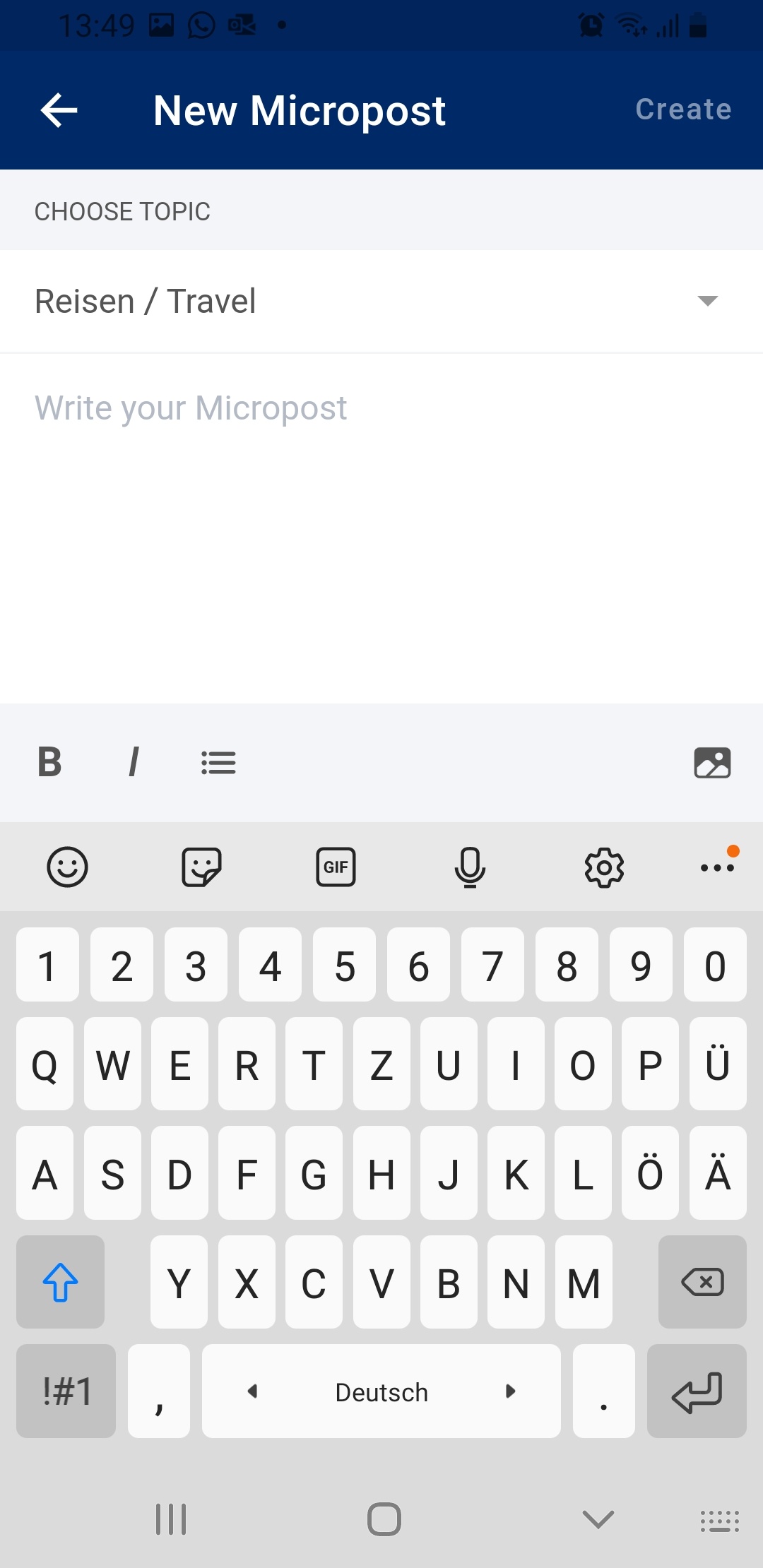

| 1. Click on the "Microblog" tab. You can create a post yourself via the plus sign at the bottom right. |

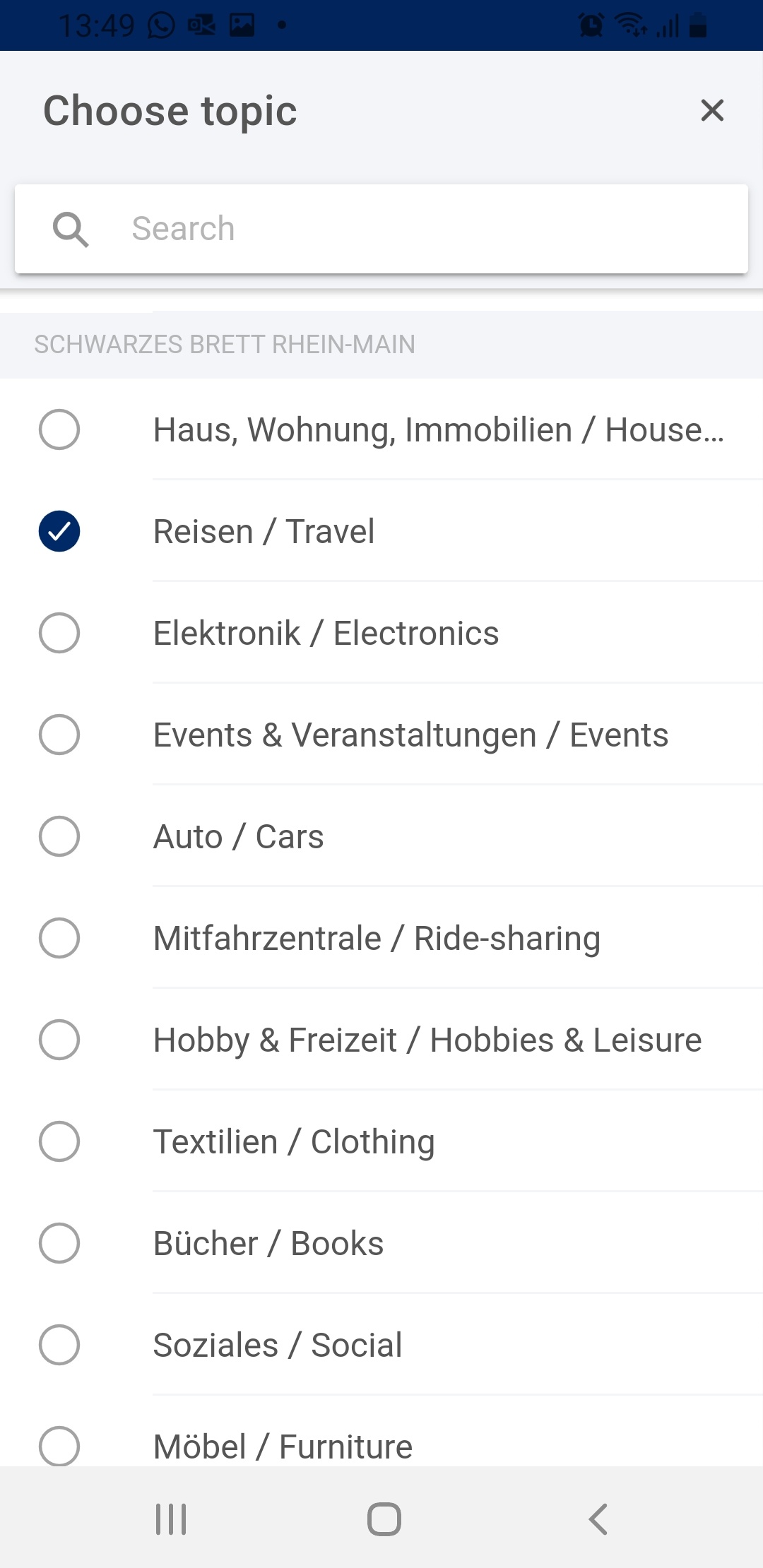

| 2. Now you see a list of all areas that have a chat. Select the desired area, e.g. bulletin board Rhine-Main, and the appropriate topic (e.g. Reisen / Travel). Make sure that you have selected the bulletin board of your region, because there are bulletin boards for different regions. |

| 3. Create your post and attach a photo or other document if needed. |

Every user of the Fred app receives the news in the "Corporate" tab. This includes Corporate News, Crisis Management News, Fred-News and the CEO blog. The news channels in the "Personal" tab are chosen by yourself. You can change which news channels you have subscribed to at any time in the desktop version. To do so, go to the Fred home page, click on "Subscribe to News" under the four news tiles. When the list opens up, you can subscribe or unsubscribe to each news channel by clicking on the star beside it.

Data Protection

No, there are no separate terms of use for the app. This is because the terms of use of the desktop version, which you have already agreed to, apply. However, with the launch of the app, we have expanded the privacy notice so that you must agree again to the known terms of use and the privacy notice expanded to include the app. Only then can you access the mobile app (the links are only available on the intranet).

The Fred app requires access to your camera so that you can log in to the app for the first time, which is done by scanning a QR code. You can remove the authorization for the camera in the settings of your device of the Fred app at any time. You can read more about the login under the question "How does the login work?" Also, the app requires access to the camera when you create a post on the bulletin board, for example. This way, you can take a photo without leaving the app, and attach it directly to the post.

Yes, the data protection department has approved the Fred app. The data protection notice was supplemented to include the Fred app and rolled out to users again.

The location query is part of the app. However, the Fred app does not collect any location data from users.

Contact

Do you encounter any technical issues or problems?

Please report it via globalservicedesk@fresenius.com.

Do you have any questions, suggestions or comments about the Fred app?

We’d like to hear them: Please message us at fred@fresenius.com

Do you have a question? askFresenius will find the answer – or someone who knows it. How? Our internal knowledge platform uses a self-learning algorithm that automatically sends your question to the right colleague.

askFresenius is our Group-wide knowledge platform. Everyone at Fresenius – from all business segments and regions – can participate. You automatically receive answers to your questions, and make new contacts.

In case you’re wondering: Language is not a barrier, because the translation function lets you translate any question or answer into your language.

You can access askFresenius here:

askFresenius is now available in the Starmind app

Before, you could only access our internal knowledge platform via your browser on your desktop and cell phone, but now askFresenius is also available within the Starmind app. The obvious advantage: Colleagues who do not always have access to a laptop due to their location, or who do not have a business smartphone, can now easily download the app to their private smartphone.

Why is the app called Starmind and not askFresenius?

Starmind is the name of the software behind askFresenius. Based on artificial intelligence, it feeds the self-learning algorithm and transports our knowledge faster from A to B. askFresenius is now part of the Starmind app, which offers all the advantages of the web version.

How can I download the Starmind app?

On business devices, use the company portal and enter "Starmind" in the search bar. After downloading, you only need to log in to the app once to get unlimited access to askFresenius.

On private devices the download is similar, the only difference being that instead of the company portal, you use either the App Store (for iOS) or the Google Play Store (for Android). Here, too, the app can be found and downloaded under the "Starmind" name. And so: Log in once, and off you go.

How does the registration in the app work?

On the login screen, you will be asked to enter the name of the network you want to log in to. Here, please enter "askfresenius" in the text field and then click on "login." You will be redirected to the Fresenius Authentication Portal, where you can select your usual login option. Enter your access data and you are already in askFresenius.

By the way, you only have to complete the login process once: You remain logged in to the app and can access askFresenius at any time without having to log in again.

Contact

Link

askfresenius.comMore information

Would you like more information or an introduction to askFresenius together with your team?

We would be happy to invite you to a webinar in your language. Email us at ask@fresenius.com

External users

You want to access askFresenius, but you don’t work at Fresenius? Sorry, but our global, internal knowledge platform is restricted to Fresenius employees. But who knows? Maybe you will be joining us one of these days. Here are our current job openings.